The recent exhibition at the Tate Modern was a huge and comprehensive retrospective of Sonia Delaunay’s vast and successful career as an artist, textile designer, costume designer, interior designer and painter. She is known for her vibrant, rhythmic and colour-filled paintings that captured and celebrated urban life, travel and the culture that inspired her.

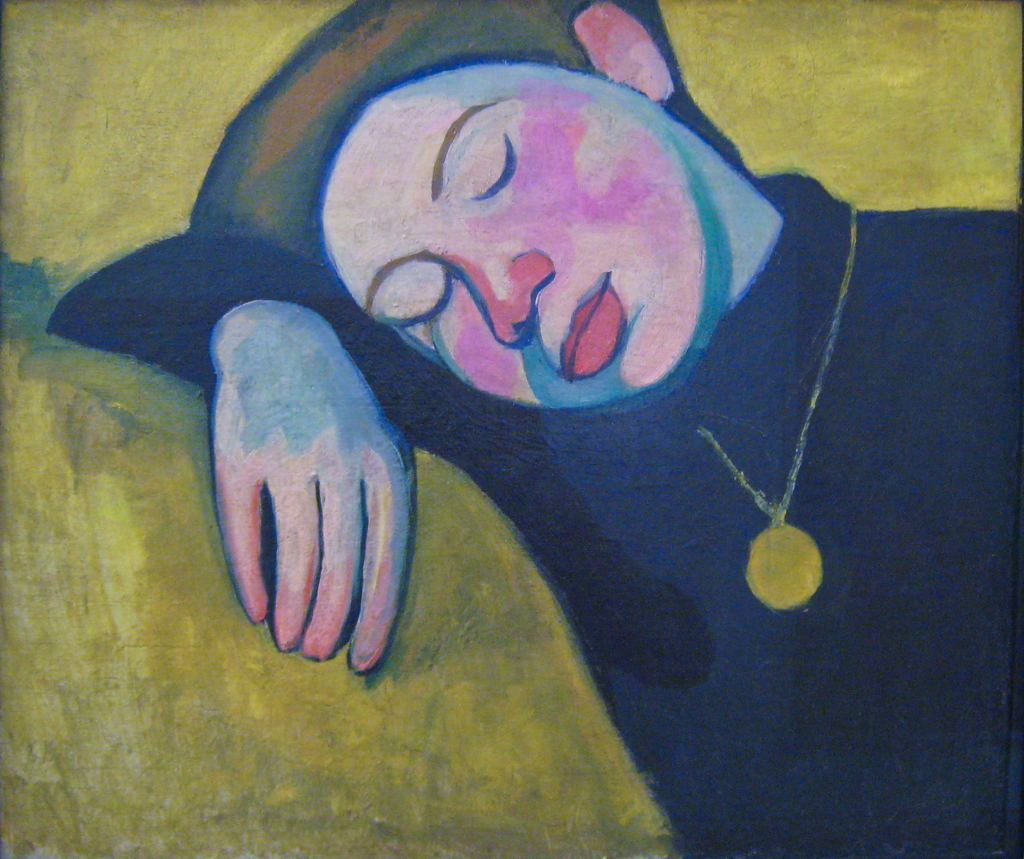

Sonia Delaunay was born in 1885 in Odessa. She attended the Art Academy in Karlsruhe in 1904, and two years later moved to Paris to study at the Academie de la Palette. The exhibition starts with Sonia’s early paintings – mainly portraits, which show a strong Paul Gauguin influence. The bold lines and vibrant colours defied the convention in painting at the time.

There is a clear move from these portraits to the abstract paintings which become more and more sophisticated as Sonia’s career develops. In 1910 Sonia married painter Robert Delaunay, which was the start of a long and successful creative partnership. Together they developed a theory of simultaneous colour contrasts which they called simultanism. This theory was applied to the Electric Prisms series of paintings in which figurative shapes are woven into a medley of bold geometric shapes that seem to be moving across the page. Indeed, many of these were results of Sonia’s evenings spent sketching in the tango dance halls in Paris that began in the early 1910’s.

As well as painting Sonia applied the simultanism theory to other medium including fabric. She stitched a patchwork quilt for the couple’s son Charles. The costumes that Delaunay designed for the Dadaist performances in Madrid while her and Robert were living there during the First World War, again show parallels with her paintings. But these costumes as well as the cot quilt appeared old and drab and the colours faded next to the vibrant and bold paintings, giving them a very different feel. However, while seeming visually inferior to paintings which are largely untouched and easy to conserve, the textiles showed a new dimension to Delaunay’s work and life. The cot quilt conveys an emotional family connection, and the costumes give a feel of the characters wearing them, stories they told and the bohemian lifestyle they were part of.

While the Delaunays were in Portugal and Spain, Sonia developed her interest in light, dynamism and colour which she expressed through her paintings of flamenco singers. Sonia opened Casa Sonia in Madrid in 1918 which sold accessories, furniture and fabrics. She also took commissions for clothing and the subsequently expanded the shops to Bilbao, San Sebastian and Barcelona. At this time she also designed costumes for the Ballets Russes production of Cleopatra, and covers for Vogue magazine.

The Delaunays returned to Paris in 1921, and by 1925 Sonia set up her own fashion house called Simultané, employing a team of Russian women to manufacture, knit and embroider her products. Sonia’s designs translated well to these other textile mediums – each one giving the patterns a new dimension. The Amsterdam department store Metz & CO. began ordering Simultané products in 1925 and the two continued a close business relationship until the 1960s. The Fashion and Textiles gallery displayed an impressive range of the Simultané designs, most framed painted designs on paper. It was a shame however, that there weren’t more draped fabrics – just a few suspended printed fabrics flat behind glass, and less than a handful of embroidered and knitted fragments behind glass. While the designs on paper were beautiful art pieces in themselves, I felt that having more fabric pieces was warranted, in order to see the designs in their context – on fabric, and make the work more accessible and tangible.

Another room was filled with the largest scale paintings of the exhibit. They were painted for the International Exhibition of Arts and Technology in Modern Life, intended to celebrate scientific innovation and boost trade. There is a distinct contrast in these paintings to the abstract and rhythmic paintings she is known for. However, you can tell it is her work, the detailed technical drawing is seamlessly combined with geometric abstract compositions, with her characteristic use of vibrant colour.

After the economic crash of 1929, Sonia returned to painting, focussing on rhythm and abstraction, continuing her geometric approach. She and Robert joined a diverse association of artists called Abstraction-Creation, with whom they exhibited and published regularly. At the onset of the Second World War, Sonia and Robert moved to the south of France. After Robert died in 1941, Sonia went to live with some artist friends in Grasse. She returned to Paris in 1945 continuing to paint in her distinct abstract geometric style.

Sonia continued with this style, joining arts organisations and groups, participating in successful exhibitions including Art Concret, Realités Nouvelles and exhibitions in New York and Germany. In her later years, Sonia continued to produce both large and small format paintings and returned to book illustration and tapestry design. The shapes used in her older paintings returned in different formats and new textures. The accompanying pamphlet to the exhibition tells us that ‘by this point, Sonia had become recognised as an essential reference for a new generation of abstract artists’. She died in Paris in 1979 at the age of 94.

The exhibition gave a comprehensive account of the works and life of an iconic artist showing a wide range of her paintings, furnishing and textile designs, costume designs, designs for tapestries and rugs, magazine covers and posters as well as for interior furnishing fabrics and fashion fabrics. We learn what an extensive and successful career Sonia Delaunay led and her talent and adaptability across mediums. I was impressed at the layout and expanse of the exhibition. I just came out feeling there was a lack of the actual textiles that took so prominent a part in Delaunay’s work, particularly in light of discussions on textiles becoming a more popular medium for many artists today, as Kirsty Bell discusses in this blog post on the Tate website.

Cover Image: Sonia Delaunay, Rythme, 1938. From: https://www.flickr.com/photos/clairity/3836520419 (Creative Commons licensed) courtesy of Sharon Mollerus