Textiles are closely connected with us as human beings and our surroundings. Indeed we rely on them to survive, for warmth and shelter. The processes, materials and qualities of textiles provide metaphors to describe the society we’re in as well as symbolising and holding affinity with important life processes.

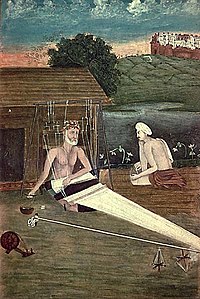

Textiles as language can be explored through history, etymology and metaphor. The metaphors of spinning appear regularly in the ancient Hindu texts including the Vedas, Upanishads explained by Puntambekar and Varadachari in their book Hand-Spinning and Hand-Weaving (1926).

‘When the poet sings his invocation to Agni, he asks of the gods “to spin out the ancient thread”. The continuity of life itself and of the human race is compared to the continuity of a well-spun thread. “As fathers they have set their heritage on earth, their offspring, as a thread continuously spun out.”’

The word tantra which has become synonymous with eroticism and esotericism within western society, in Indian traditions applies to “text, theory, system, method, instrument, technique or practice.” That the Sanskrit term translates to ‘weave, loom and warp’ suggests the interweaving of traditions and teachings as threads into a text, technique or practice. The Hindu God Vishnu is called tantuvardan or ‘weaver’ because he is said to have woven the rays of the sun into a garment for himself.

Jumping forward about seventeen centuries, we see again multiple metaphors woven into the poems of Kabir, the revered weaver-poet who was born into the julaha weaving caste in Banaras, India. Kabir compares the act of weaving to that of creation:

You haven’t puzzled out

any of the Weaver’s secrets

it took Him

a mere moment

to weave the Universe

on His loom

– the first paragraph of The Master Weaver, taken from The Weaver’s Songs by Vinay Dharwadka (2003)

The metaphor of text as a woven fabric has been explored by philosophers Jacques Derrida, Roland Barthes and Julia Kristeva. Textiles and Text share the same latin origin: the verb texere which means ‘to weave’, and it is believed that textiles could have been a form of language before the advent of writing. Tim Ingold in his writings on Lines, reflects that ‘line began as a thread rather than a trace, so did “text” begin as a meshwork of interwoven threads rather than of inscribed surfaces’.

Victoria Mitchell says ‘in the Andes the language itself – Quechua, is a chord of twisted straw, two people making love, different fibres united’, and that the Hungarian word for fibres is the same as that for vocal chord. ‘These fragile references suggest for textiles a kind of speaking and for language a form of making.’ We can see textiles’ strong affinity with song in the characteristic of patterns they both share. Professor Janis Jefferies has researched the correspondences between patterns found in weaving and those found in traditional polyphonic songs. Like individual threads, the individual voices each are contributing to a textural and harmonic whole, whether physical patterned cloth, or melodic, textured sounds.

In many traditional weaving communities, song is an important accompaniment to the act of weaving. The loom acts as a sort of instrument, creating a rhythmic and repetitive accompaniment for the weaver to sing along to while involved in the repetitive, physical movement of weaving. To quote Mitchell again: ‘through the senses, touch and utterance share common origins in the neural system and in the pattern of synaptic, electro-chemical connections between neurons.’

This connection is evident in Deepak Mehta’s anthropological study of Muslim Ansari weavers in Banaras. In Work, Ritual, Biography, Mehta describes the practice of weavers reciting du’as, Islamic prayers while at the loom. Within the du’as are answers to questions that Adam asks Jabrail when the first loom is introduced from heaven. ‘In uttering (the du’as) the weaver invokes the loom as memory…to weave is to pray, to pray is to weave’. Like Kabir who is said to be of the same community as the weavers in Mehta’s book, weaving is sacred, almost as sacred as creation itself.

While perhaps not as religiously and ceremoniously intrinsic to their craft as for the Ansari weavers, song is or has been in the past, an important accompaniment to weaving practices all over the world. Before industrialisation brought mechanical weaving to Scotland, handloom weavers would sing Gaelic songs while waulking tweed. The tune would follow the rhythm of beating the cloth which all the women would do in syncopation, as shown in this video, probably alleviating the tediousness of the process. Songs sung during work in weaving or other pre-industrial crafts, like sea shanties, slave songs and prison work songs were ‘used as tools in the labour process, adopting rhythms and performance styles appropriate to the specific physical movement required.*

In some textile traditions, particularly processes which require more concentration, song is used to communicate the design or help the maker remember the sequence. This has been found by David Hopkins in his research on singing by lacemakers in Victorian Britain and other parts of northern Europe. Anthony Tuck also discusses songs sung by weavers in parts of Central Asia and Persia which communicated information regarding the thread or knot colour and its relevant count position on the warp of a loom. The graph designs for woven patterns share striking similarities to musical manuscript, again pointing towards the shared characteristics of song and textile mentioned above.

Embroidering the social fabric

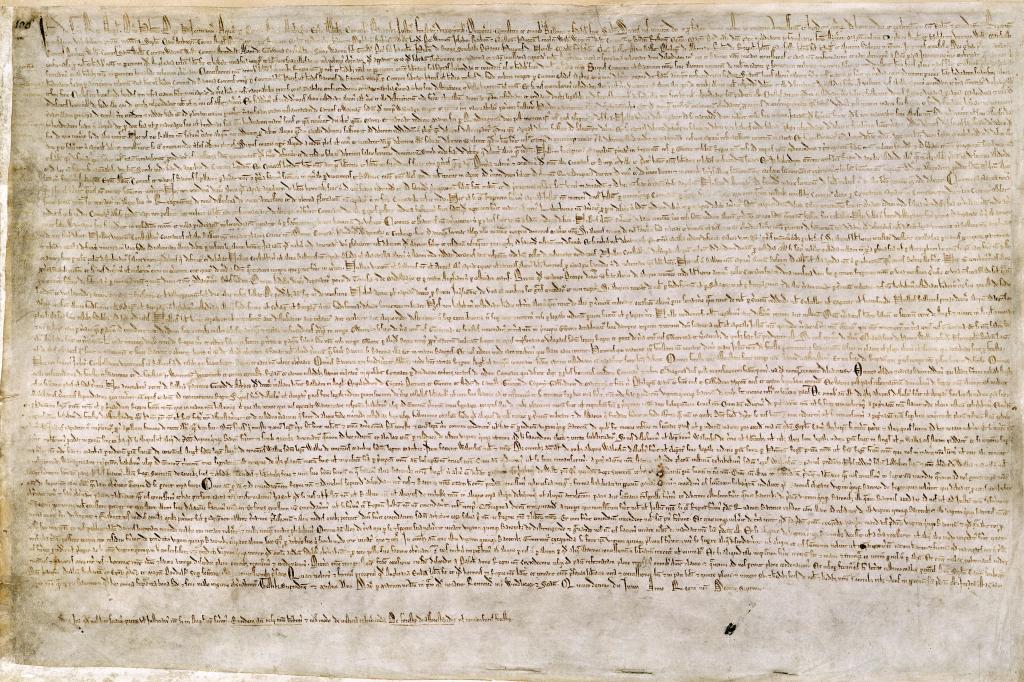

Accompanying the current exhibition Magna Carta at the British Library, is the Magna Carta embroidery by Cornelia Parker. This exemplifies the relationship of textiles and text, and textiles as a form of communication, in a more literal way. It does more than that though; the 13 metre long textile is an embroidered replica of the Wikipedia’s article on the Magna Carta. It symbolises the collective voice of the people on civil liberties. The fabric, printed with the article was divided into sections and sent to 200 people to stitch. The detailed accompanying images were stitched by professionals at the Royal School of Needlework, and the bulk of the text was stitched by prisoners under supervision of Fine Cell work – a social enterprise that teaches needlework skills to prisoners as a form of therapy.

Textiles, Emotion and Touch

Textiles are strongly associated with touch. Traditionally a cloth would have passed through many different hands, representing the epitome of hand-made. During London Craft week, weaver Catarina Riccabona was demonstrating her weaving on a small traditional frame loom in St James’ Church in Piccadilly. Catarina was eager to discuss her work with others. She is fascinated by the extensive interaction between the yarn and her hand –as she prepares the warp every single inch passes through her fingers. Through this process, the final piece of cloth almost contains a part of the maker, giving it value through the care involved, and a strong human connection. To then wear the finished piece of cloth, the wearer is sharing the experience of the maker. ‘(textiles) are most closely known to us through their relationship to the skin and to the sense of touch, a sense which is actively encountered through the making of textiles by hand’ – Victoria Mitchell.

Another feature of textile is its ability to reveal and conceal, a feature that fascinates artist Richard Tuttle, and a theme that he explores in his textile based art works. Tuttle’s work was showcased at the Whitechapel Gallery, and the Tate Modern earlier this year. I don’t know. The Weave of Textile Language, demonstrates Tuttle’s fascination for textiles and their afinity with language. Magnus Af Petersens, in the accompanying catalogue states that while many artists are inspired by textiles and collect them, they are often viewed in the craft sphere and separated from the artist’s own fine art practice. For Tuttle on the other hand, they form a crucial medium of expression.

As well as an artist and textile collector, Tuttle is also considered a poet. Petersons goes on to say that through his poetry, Tuttle considers the materiality of language, with the typography and design of the page as vital elements of the poetry.

‘Wire pieces’ represent the smallest and most delicate constituent of textiles, the single thread. In contrast, Tuttle’s installation in the a turbine Hall of the Tate gallery consists of a large wood and textile structure, taking over most of, and transforming this massive space. However it is not size that Tuttle is concerned about, although it is a tool to achieve his desired scale, moreover Tuttle is concerned with textiles and their relationship with everything else. Swathes of deep red and bright orange heavy fabrics are wrapped around and hung from a huge wooden machine-like frame with lights shining on the fabric at regular intervals, multiplying the colours.

Tuttle sourced his fabric from Garden Silk mills in Surat, India, a region with a long and rich history of textiles production, and today the region has the largest powerloom industry in India. To me, this installation represents the domination of mass manufactured textiles, and in turn crude and unrelenting machinery, over the fragile, culture rich traditional handloom textiles, that Tuttle’s smaller pieces such as the wire pieces represent. However,Tuttle argues that despite a broad negative perception that machines are imitating the hand made (which does happen), the machine can work in different ways, producing different aesthetics and qualities. While the hand-made textiles that Tuttle collects and is inspired by are carefully preserved and exhibited in museums and galleries, on a par with ‘high art’, machine-made fabric is cheap and taken for granted all over the world. Tuttle is exploring the perception and value for textiles and art. In using textiles for a piece of art, is the value of the textiles used increased, or the status of the art work reduced?

More on this subject in my next post which will come after I return to the Tate to see the retrospective of Sonia Delaunay’s work, another artist for whom textiles was an important medium.

Mitchell, V. (2012) ‘Textiles, Text and Techne’, in Hemmings, J. (ed.) The Textiles Reader. London, New York: Berg, pp. 5-13.

Puntambekar, S. V. and Varadachari, N. S. (1926) Hand-Spinning and Hand-Weaving. Ahmedabad: All India Spinners’ Association.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tantra

Mehta, D. (1997) Work, Ritual, Biography. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

I don’t know. The Weave of Textile Language. (2015): Tate Publishing, Whitechapel Gallery.

Robertson, E; Pickering, M; Korczynski, M, (2008) ‘And Spinning so with voices they meet, like Nightingales they sung full sweet’, Unravelling representations of singing in pre-industrial textile production, in The Journal of the Social History Society, 5:1, 11-31

Tuck, A. (2013) Singing the Rug: Patterned Textiles and the Origins of Indo-European Metrical Poetry, Chapter One in The Anthropology of Performance: A Reader, Koro, Frank, J. Wiley-Blackwell

4 Comments

sonia

Hi Ruth,

Just a quick line to tell you how joyous your blog posts are to me! As a textile enthusiast, I admire your formal research endeavor–it is a labor of love…

Your sharing style in easy, ‘personal essay’ flow with pictures and anecdotes makes the reading experience really rich and interesting–I look greatly forward to sitting with a cup of tea to read and often re-read your accounts of travel and discovery!

I’ve always been fascinated by the metaphor of weave, so this particular post is super exciting.

many thanks for sharing. Warmly, Sonia.

Hi Sonia,

Thanks for your kind words. I’m really glad to hear that you enjoy my blog posts. I love writing them, but don’t always know if they’re actually interesting to people, so it’s so nice to get the feedback!

Best wishes,

Ruth

Leonore Alaniz

Dear Ruth, I too appreciate deeply this blog and what you pour into it. I will share more in the future, but didn;t want to miss this oportunity to let you know that thispst is very relevent to my work as weaver: In a recent solo exhibit I explored – and related to the public – the metaphors o thread, cloth, loom, the act of weaving. Kabir was a self-realized yogi. In the book (you pointed out to us) “the Weaver’s song”, he decribes the fine thread, so fine, and means the thread of prana weaving around the shushumna (so the author explains), and he refers to the stages the fetus in the mother’s womb. Did you realize this? I tried to order the book but aside from a $1700 example, it is not avaialble. This is the title: Kabir, Spiritual Commentary; recorded by Sri Sri Shyamacharan Lahiri Mahasya (who was initiated by Babaji into Kirya Yoga; see also Aurobiography of a Yogi by Paramahansa Yogananda). the english tranlation of Lahiri’s work is by Yoga Niketan.

Safe Travels t you, Ruth. I m grateful I found you online! Leonore Alaniz.

Hi Leonore,

I’m grateful to hear from you too, and its really nice to hear that you appreciate my blog. Your work sounds fascinating and I’d have loved to see your exhibition. Which poem do you refer to in the ‘Weavers Song’ book? I will have a look again. I’ve read Yogananda’s book and really enjoyed it. I hadn’t realised that his Lahiri Mahasaya had written on Kabir.

Thanks again,

Ruth