Assam is one of the seven (or arguably eight) states in North East India, set in the Brahmaputra basin, tucked away just south of the Himalayas, attached to mainland India only by a thin strip of land. Textiles here hold more similarities with neighbouring North Eastern states and with other countries further east and in South East Asia, which they are geographically and culturally close to, than woven textiles in mainland India which have distinctly different traditions and cultural approaches. The tribal textiles of Assam are woven predominantly by women for whom learning to weave and becoming a proficient weaver is a rite of passage and a required attribute to be accepted into marriage. The wrap skirts woven for their own or family wear, not usually for sale, incorporate motifs, patterns and colours distinct to their particular community.

Another cloth seen in urban Assam is plain woven muga silk which is indigenous to Assam and not produced anywhere else. It has a natural honey hue and is valued almost as much as gold. Eri silk is also produced in Assam, as well as other regions in the North East.

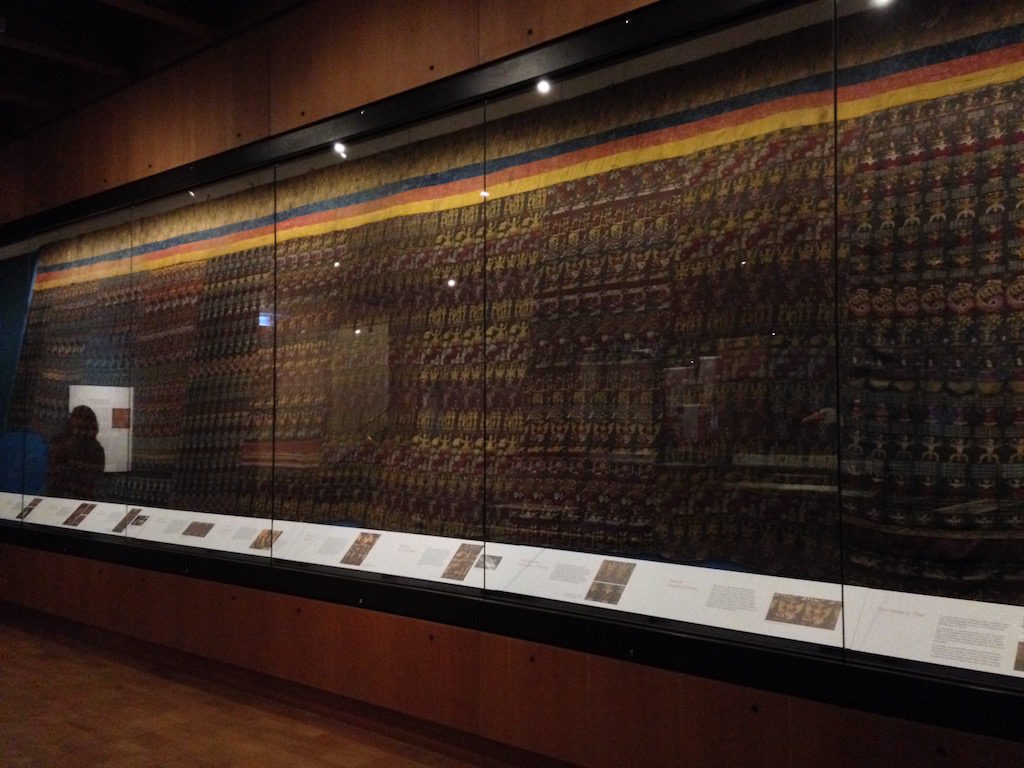

The textiles that are much less known and written about however, and only produced over a short period in the middle ages – according to Rosemary Crill[i] the first were around 1567 – 69, are the Vaishnavite Silks, or Vrindivani Vastras (cloth of Vrindivan – a forest in Northern India where Krishna is believed to have lived early in his life). The few surviving examples exist in private collections, the Calico Museum in Ahmedabad, and the British Museum which is displaying these for the current exhibition ‘Krishna in the Garden of Assam’. The ones on display in the British Museum were discovered in a Buddhist temple at Gobshi in southern Tibet where they had been used as borders on thangkas hung in temples. Crill tells us ‘the Vaishnavite ritual significance of these textiles is the key to their original existence’. They were commissioned for Prince Chilarai of Cooch Behar under the supervision of the great Vaishnavite reformer Sankaradeva, who lived in Barpeta, Assam for the last 25 years of his life. Chirali wanted Sankaradeva to supervise the weaving of a scroll depicting Krishna’s life.

Images depict scenes of Krishna wandering in the forests of Vrindivan, with his beloved gopis (cowherdesses), or killing demons in various animal forms. Some pieces show scenes from the Ramayana and avatars of Vishnu such as Rama, Matsya the fish, Kurma the tortoise, and Narasimha, the man-lion. Interestingly, Sankaradeva disapproved of the use of figurative imagery in temples and wanted the focus of workshop to be on the Bhagavata Purana – the text that tells the story of Krishna. Thus the Vrindivani Vastra was used to cover the manuscript and was draped over the thapana – altar on which it was placed.

The dramatic nine-yard cloth is made up of twelve individual silk strips stitched together, each woven in the complex lampas technique. These would previously have been used to wrap the Bhagavata Purana. This labour intensive technique, now virtually extinct all over the world involves weaving one set of warp and weft threads in the ground and the pattern woven in another set of warp and weft threads to allow for multiple colours. It is not certain how the technique of lampas began to be used in Assam, an area not usually known for lampas, and where there was no long standing tradition. Crill refers to Stephen Cohen who suggests weavers producing lampas in Bengal could have established the technique in Assam. Rahul Jain said to me once he thinks the technique could have even originated in Gujarat and travelled to the North East from there. Indeed, Gujarat is the one other centre famous for the technique. There is unfortunately scant detail on the lamps technique in the exhibition, with more focus being held on the story depicted.

There are no definite explanations as to how these arrived in Tibet, although there was an easy trade route from Cooch Behar to Tibet via the valley of the River Tista up to Gangtok and Yatung. But Indian silks were highly prized in Tibet and Assamese merchants are known to have traded silks with silver and salt. These textiles are amongst many that have moved from country to country through trade and the movement of peoples and sharing of influences.

The Vrindivani Vastra then was acquired by Perceval Landon, a Times newspaper reporter covering the British military expedition to Tibet in 1903-4. We don’t know how he acquired it though (hopefully by payment!). Landan presented the textile to the British Museum in 1905, but it was only correctly identified in 1992 as the Vrindivani Vastra.

The exhibition goes on to explain the various scenes in the cloth. The text in the cloth is a section of the play Kali-damana written by Sankaradeva telling the story of the defeat of the demon Kaliya by Krishna. The drama continues to be performed every October during the annual festival Ras Lila. The exhibition includes film clips of the play Kali-damana, being enacted in the modern day, models of the masks worn in the play, examples of how Vaishnavite textiles have been re-used and examples of what most know as the typical cloth of Assam.

The Banyan gown is the most impressive of the pieces that show the re-use of a Vaishnavite textiles, which features as the lining, and its outer is made up of Chinese floral damask. The gown would have been worn by wealthy European gentlemen living in Asia. The gown was restored and loaned by Chepstow Museum.

The contemporary pieces include the Gamusa, white woven cloth with red patterning usually worn as a scarf or to wrap turbans or other objects. It is also often gifted to visitors as sacred objects.

There are lengths of muga silk skein on display. Muga is from the antheraea assamensis moth which is common only to Assam. Ladies traditional garments, the mekhela (lower garment) and chador (upper garment) are woven with muga and the centre for weaving muga is Suallkuchi. In the forthcoming symposium at the BM which accompanies the exhibition, a documentary film on muga produced by Leona Chahila will be shown. Leona documents the struggle the country of Assam faces as it continues to define an identity, stuck in a state of in-betweenness. Textiles though are the one constant of the country, continuing to be woven and held in high symbolic and cultural importance .

The exhibition is on until the 15th August at the British Museum, and the symposium will be held on the 9th July.

[i] Crill, Rosemary, Vaishnavite Silks: The Figured Textiles of Assam, Rosemary Crill, in The Woven Silks of India, Marg, 1995, ed. Jasleen Dhamija

Further Reading

Blurton, Richard, Krishna in the Garden of Assam: The History and Context of a Much-Travelled Textile, 2016, British Museum

Dhamija, J and Jain, J. Handwoven Fabrics of India, 1990, Grantha Corporation

Kapur Christi, R and Jain, R. Handcrafted Textiles: Tradition and Beyond, 2000, Roli Books